How we lost our collective memory of epidemics

Doctor Explains: How Cerebral Malaria Can Turn A Mosquito Bite Into A Life-threatening Emergency

Cerebral malaria, a severe complication caused by Plasmodium falciparum, can quickly escalate from a mosquito bite to a life-threatening brain emergency. Firstpost brings out an expert's view on how the parasite invades the brain, the early warning signs like seizures and coma and why rapid diagnosis and intensive treatment are crucial to prevent permanent neurological damage or death. Read more

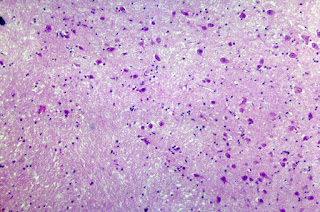

Cerebral Malaria is a severe neurological condition caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which is transmitted through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes. This form of malaria affects the brain, leading to various serious symptoms and complications.

Firstpost talked to inputs by Dr Anurag Aggarwal, Consultant, Internal Medicine, Fortis Escorts Hospital (Faridabad) to know how it develops, its warning signs, diagnostic methods, treatment options and the urgent need for preventive measures.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW THIS AD World Malaria Day: Why India's fight against malaria requires more than just medicine Causes and transmissionCerebral Malaria is primarily caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum. When an infected mosquito bites a human, the parasites travel to the liver, where they multiply before invading red blood cells. As the parasites continue to reproduce, they cause the red blood cells to become sticky and clump together, blocking the small blood vessels in the brain. This obstruction reduces blood flow and leads to brain swelling, which is the hallmark of cerebral malaria.

SymptomsThe symptoms of cerebral malaria can appear as early as 7 days after exposure. They include:

- Severe Headache: Initially, patients may experience intense headaches.

- High Fever: A high and recurrent fever is one of the primary signs.

- Seizures: Convulsions or seizures may occur due to the brain's involvement.

- Coma: In severe cases, patients can fall into a coma, a critical condition that requires urgent medical attention.

- Neurological Deficits: Symptoms like confusion, behavioral changes, and impaired movement can occur.

Accompanying these core symptoms, patients might also experience nausea, vomiting, and general malaise. Due to its ability to swiftly progress to severe illness, early detection and treatment are crucial.

DiagnosisDiagnosing cerebral malaria involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory tests. Blood smears can reveal the presence of parasites, while rapid diagnostic tests identify specific malaria antigens. MRI and CT scans can detect brain swelling, and other neurological assessments may be performed to gauge the level of brain involvement.

TreatmentImmediate, aggressive treatment is essential to combat cerebral malaria. The main line of treatment is intravenous antimalarial drugs, such as artesunate or quinine. Supportive care, including managing seizures and maintaining adequate oxygen levels, is critical. Patients may require intensive care support due to the severe complications that can develop.

PreventionPreventive measures are vital, especially in malaria-endemic regions:

- Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets: Sleeping under treated nets can significantly reduce mosquito bites.

- Preventive Antimalarial Drugs: Prophylactic medication is recommended for travellers to high-risk areas.

- Indoor Residual Spraying: Applying insecticides indoors can prevent mosquito breeding.

- Protective Clothing and Repellents: Wearing long sleeves and using mosquito repellents can lower the risk.

Prognosis and complicationsWith timely and appropriate treatment, the prognosis for cerebral malaria can be good; however, delays can lead to severe complications, including irreversible brain damage or death. Children and pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to the worst outcomes.

Cerebral Malaria is a severe and potentially fatal condition that requires immediate attention and treatment. Its prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia and Latin America necessitates robust preventive measures and awareness to reduce transmission. Understanding its symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options is crucial for both individuals residing in and traveling to endemic areas.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW THIS ADEducating communities and improving access to healthcare can help mitigate the impact of cerebral malaria, ultimately saving lives and improving health outcomes in affected regions.

End of Article

Urgent Change Needed To Prevent Malaria And Meningitis Deaths In African Children

Fever and coma are commonly seen in African children, caused by malaria of the brain, followed by bacterial meningitis. However, these diseases have very similar symptoms, and the limited diagnostic testing makes them challenging to diagnose and treat.

The research, published in The Lancet Global Health, is the most extensive analysis of febrile non-traumatic coma in children on the African continent to date.

One in four African children with malaria and coma has an additional infectionThe researchers analysed two parallel studies: The aetiology, mortality and disability of non-traumatic coma in African children: A systematic review and Aetiology, neuroradiological features, long-term neurosequelae and risk factors for mortality of febrile coma in Malawian children: A prospective cohort study.

The first study reviewed all previous studies for non-traumatic coma in African children and found that the death rate due to malaria infection has remained unchanged for nearly fifty years, with almost one in every five children dying. This is despite years of research and interventions such as bed nets and improved treatments.

The second study found that cerebral malaria is the leading cause of febrile coma and that co-infections complicated over a quarter of cases. These infections were mainly bacterial and detected through molecular tools. The research showed that children with malaria and bacterial meningitis co-infection were more likely to die, compared to those with malaria alone, and the risk of death was even greater if co-infected children did not receive antibiotics.

These findings highlighted the urgent need to re-consider frontline management for children who present with fever and coma and indicate the critical need for immediate antibiotics (alongside antimalarials), irrespective of malaria diagnosis.

Dr Stephen Ray, Principal Investigator at the Oxford Vaccine Group led the study alongside Dr Charlotte Fuller, from the Brain Infection and Inflammation Group at the University of Liverpool.

Dr Ray said: "Too often malaria parasites found in the blood of a sick African child stop medical staff from looking for and treating additional bacterial infections. A positive malaria test commonly leads to only treating the child with antimalarials, and therefore it becomes a risk factor for children to die from untreated bacterial infections. Our study found there were frequent bacterial infections, often alongside malaria, and these results emphasise the need for immediate antibiotics to be given to all children presenting with fever and coma, even if they have a positive malaria test. Our hope is that these findings cause a change in practice and save lives".

The findings will support the World Health OrganizationThe researchers performed an MRI at admission and identified that 90% of children had a brain injury and 50% had brain swelling at hospitalisation. They also found most children with meningitis had severe complications, such as intracranial pus, that could have been treated earlier with neurosurgery.

Additionally, the team performed face-to-face neurological follow-up assessments with survivors and identified a disability in half of these children. The findings support an update of national and WHO guidelines on severe malaria and coma, and changes to clinical practice.

University of Liverpool's Dr Charlotte Fuller said: "Our cohort study highlights the value of molecular and radiological diagnostics in managing life-threatening brain infections. The frequent complications found on admission brain scans illustrate that earlier escalation to specialist care, with neurosurgical capacity, maybe most critical. Further work is needed to facilitate widespread deployment of affordable molecular and radiological diagnostics across the African continent".

Combining Antibiotics And Antimalarials Could Significantly Lower Child Malarial Deaths: Research

Researchers recommend PCR testing and administering antibiotics alongside antimalarials to improve the diagnosis and outcomes of malarial coma in children

Two parallel studies published today in The Lancet Global Health reveal new insights and approaches that could significantly lower the number of febrile coma deaths in children, often caused by malaria.

Febrile coma – the simultaneous presence of fever and coma – is a common reason for hospital admission among African children, with malarial infection of the brain being the most frequent cause, followed by bacterial meningitis. Accurately differentiating between the two conditions and administering the right treatment is often challenging, as they present with similar clinical features and diagnostic tools are frequently limited.

Led by researchers at the University of Sydney, the studies present findings from the largest analysis to date of febrile coma in children on the African continent.

The first study found the death rate from febrile coma among African children has remained unchanged for nearly 50 years, with nearly one death per every five children. This is despite decades of research and health interventions to reduce overall malarial illness, such as bed-nets, rapid diagnostics for malaria and improved antimalarial drugs.

According to the World Health Organization, there were almost 600,000 malaria deaths globally in 2023. Africa carries a disproportionately high share of the global malaria burden, with 95 percent of all deaths. Of the region, children under five accounted for about 76 percent of all malaria deaths.

The second study found that among children with malarial coma, co-infection with bacterial meningitis is a key cause of death. It also showed that by treating co-infected children with a combination of antibiotics and antimalarial drugs significantly reduced child mortality by fivefold – from 57.3 percent to 10 percent.

The studies were led by Professor Michael John Griffiths, Director of the Centre for Child and Adolescent Health Research and Professor of Paediatric Neuroscience in the University of Sydney's Faculty of Medicine and Health, whose team gathered evidence for the research while working at the Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi.

"Administering antibiotics to children with malarial coma offers to significantly reduce mortality compared to those who do not receive them," said Professor Griffiths.

"Children presenting to health centres with febrile coma usually have no specific clinical signs or symptoms to determine the underlying cause. As a result, detection of malaria often leads to the child being treated solely with antimalarials.

"Our study, however, shows that bacterial infections frequently occur alongside malaria. These findings highlight the need for immediate antibiotics combined with antimalarials for children presenting with febrile coma. We hope that our results will support an update to national and WHO guidelines on severe malaria and coma, as well as stimulate changes in clinical practice."

Among the Malawian children studied, the researchers found that using tools like pathogen-specific PCR tests dramatically improve the detection of pathogens among children with febrile coma by fifteen-fold compared with standard microbiology.

"Pathogen-specific PCR tests are increasingly cheap, easy-to-use and provide almost instant results, making them the ideal diagnostic tool in underserved areas. On the frontline, there often aren't the local resources for culture samples to be processed in a microbiology laboratory, which are often limited to central hospitals," Professor Griffiths said.

The most common bacterial co-infection types were streptococcus pneumonia and non-typhoid salmonella, which typically respond to commonly available antibiotics, such as ceftriaxone.

"The use of antibiotics always raises the concern of antimicrobial resistance. However, a child presenting with deep coma or fever and a high risk of death justifies their use," he said.

Through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain in children with malarial febrile coma, the researchers also found a high prevalence of brain abnormality, suggesting significant brain damage.

"Compared to brain imaging of children presenting with meningitis in higher resource countries, the children in our study appear to have more frequent and extensive acute brain abnormalities, potentially suggesting severe and/or protracted illness prior to hospital presentation," he said.

The researchers recommend the practice of administering antibiotics with antimalarials be promoted in both local and global World Health Organisation guidelines. They also recommend greater uptake of molecular tools like PCR tests to improve diagnosis and treatment.

"Improving access to healthcare for children with severe coma, through better education and infrastructure, could lead to earlier treatment and save even more lives. Ensuring that health units are equipped and accessible is also key to reducing preventable deaths," he said.

"It's true that many underserved areas lack in resources, but with this comes a great resourcefulness. Tapping into this trait, taking a pragmatic approach and making use of what's readily available – in this case antibiotics and rapid testing – could drastically improve health outcomes. After so many years, this might be just what begins to shift the dial on malaria."

Key findings

Comments

Post a Comment