Evaluating pediatric risk after BRUE - EMS1.com

By David Wright, M.S., PA-C, NRP; and Kate Randolph, B.S.

You and your partner are responding to a 911 call. Dispatch informs you that an alarmed new mother has a 6-week-old premature infant who had a 2-minute episode of lethargy.

When you arrive on scene, that mother is now calm and states her baby looks much better at this time. You evaluate the patient and obtain further history. The patient's mother informs you that the patient was born prematurely at 31 weeks and 4 days, and admitted in the NICU for 5 weeks. The patient was just discharged 4 days ago. Today, while holding the patient, she noted that he suddenly stopped breathing and became limp. Even though she was not feeding the child at the time of the episode, she performed some back blows, but nothing changed. She called 911 and noticed that the baby had a bluish color around the lips and in the fingers and toes.

Your current physical exam shows a very well-appearing infant, with good tone, pink color and normal capillary refill time. You obtain a set of vital signs and note them all to be within normal limits for his age. You start to wonder what happened, when your partner reminds you about brief resolved unexplained events (BRUEs) and their need for transport to the ED.

Brief resolved unexplained event (BRUE)

BRUEs can be very concerning for not only the guardians of a patient, but also the

clinicians involved in the patient's care. A BRUE is defined as an event in patients younger than 1 year of age, that is an acute, short and now resolved episode of at least one of the following symptoms [1]:

It is extremely important to understand that this is classified as a diagnosis of exclusion. This means that this diagnosis should only be applied when the clinician has performed a thorough history and physical exam, and if indicated, diagnostic testing has been performed.

BRUE signs and symptoms

BRUE symptoms include:

- Cyanosis or pallor

- Absent, decreased or irregular breathing

- Marked change in tone (hyper or hypotonia)

- Altered level of responsiveness

The patient must be <1 year old and have no other explanation for the event for the incident to be considered BRUE.

BRUE epidemiology

First described in 2016, BRUEs are a relatively new diagnosis, making the estimated incidence of BRUEs currently difficult to assess under the new criteria. Prior to 2016, BRUEs were classified under the apparent life-threatening events (ALTE) diagnosis. It should be noted that BRUE is more than just the new term for ALTE [2]. One study revealed only 1 out of 78 reviewed cases that met the criteria for ALTE also met the criteria for BRUE. The other 77 cases had explainable events that had explainable causes [3]. The study of ALTEs is more readily available for evaluation of frequency of occurrence. Such studies indicate that ALTEs occur in 3:10,000-41:10,000 infants [4]. This wide range could be the result of the broad definition of ALTE. It is likely that studies implementing the more narrow definition of BRUE will shift the diagnosis explanation [4]. The influence of race, gender, ethnicity, environmental factors, and social status associated with BRUEs are also being reviewed [2].

Low vs. high risk BRUE

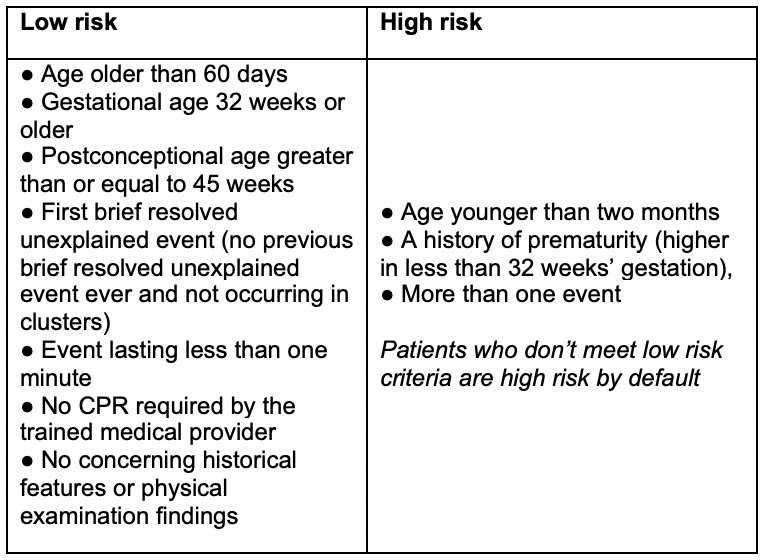

Using the BRUE definition, infants younger than 1 year of age who present with a brief, sudden and now resolved episode are categorized as a lower risk or higher risk. This is based on history and physical examination [5]. Infants defined as lower risk are older than 60 days of age and have no requirement for cardiopulmonary resuscitation by the medical professional.

Lower risk BRUEs last less than one minute with no repeating or previous BRUE events, no concerning medical or family history, as well as no concerning findings during a physical examination. With the lower risk infants, the medical professional may educate the caregiver about BRUE and offer additional resources, but do not need to do any additional medical testing.

Infants defined as higher risk are younger than two months of age, a history of prematurity, and those with repeating events. If the clinical history and/or physical examination of the patient reveals abnormal findings or other concerns that the patient is at higher risk, then the patient should undergo further investigation/treatment. Higher risk infants are more likely to have an underlying cause, recurring events or abnormal outcomes and findings [5].

Table: Signs and symptoms for low vs. high risk BRUE [1]

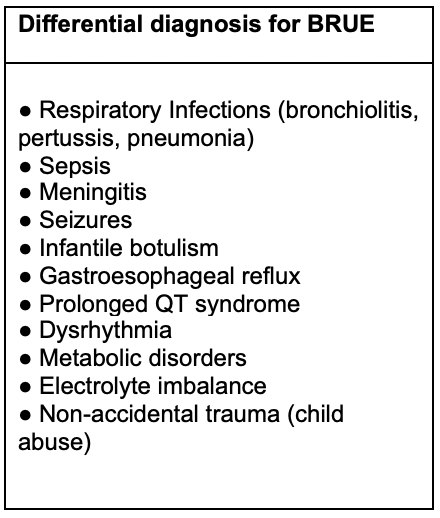

Differential diagnosis for BRUE

As BRUE is a diagnosis of exclusion, it is important for the clinician to rule out other etiologies. It is important to point out that many causes cannot be ruled out in the current pre-hospital setting.

- Respiratory. Upper and lower respiratory infections (bronchiolitis, pertussis and pneumonia can all cause apnic spells)

- Hematologic. Sepsis

- Neurological. Meningitis, seizures, infantile botulism

- Gastrointestinal. Gastroesophageal reflux

- Cardiac. Prolonged QT syndrome, dysrhythmia

- Endocrine. Metabolic disorders, electrolyte imbalance

- Trauma. Child abuse

Immediate BRUE treatment by EMS

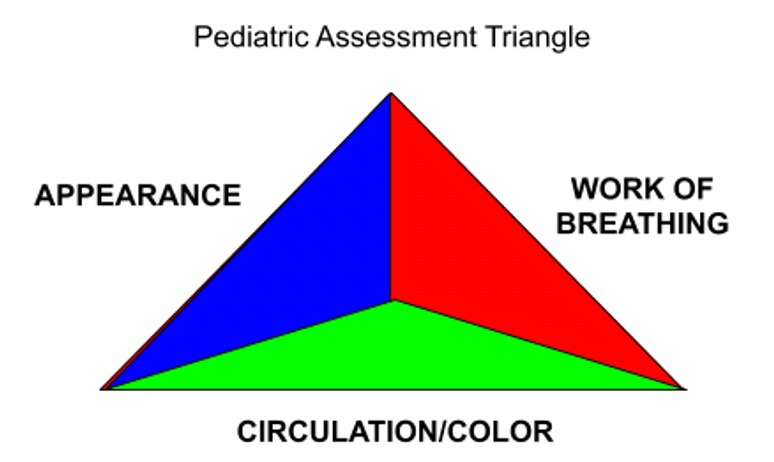

Initial EMS treatment is based on how the patient presents on your arrival. As with any patient, it is important for the EMS clinicians to perform a thorough physical assessment. Initial assessment should begin with utilization of the pediatric assessment triage. This helps accurately predict the severity of a child's illness and your primary assessment [6]. Recall your pediatric assessment triangle (PAT) consists of the three following components [7]:

- Appearance. Initially ask yourself "what does the patient look like?" Clinicians should be evaluating the patient's tone, ability to interact, consolability and their speech/gaze before even touching the patient.

- Work of breathing. The patient's respiratory status should be immediately evident to the clinician upon first encounter. ...

Comments

Post a Comment